HyperText Markup Language (HTML) is the web’s foundation. It tells browsers how to structure a page’s content—headings, paragraphs, images, lists, and more—so people and search engines can understand it.

“Structure” is the keyword. As the name implies, HTML isn’t a programming language—it’s a markup language. Your HTML describes what each piece of content is (a heading, a list, a navigation link), not how it computes.

By contrast, programming and scripting languages—like Java and JavaScript—use logic and variables to tell software how to behave. JavaScript runs in the browser (and on servers with Node.js) to respond to user interactions, fetch data, and update the UI. Java is typically used for backend services, Android apps, and large systems.

All three categories—markup, scripting, and programming—work together in modern web development. Some sites stay simple; others combine many layers for richer experiences.

Isn’t Any Website an Example of an HTML Website?

Technically, yes. Every page that renders in a browser uses HTML. Most sites, however, pair HTML with other languages to enhance design, interactivity, performance, and accessibility. Think of HTML as the skeleton; other layers provide the muscles, skin, and senses.

Should you build a static HTML website with nothing else? Generally, no.

Today’s web standards expect responsive layouts, fast performance, and accessible, interactive interfaces across devices. That typically means adding CSS for presentation and JavaScript (and often a backend language) for functionality.

If you’re a beginner looking to set up your first website, check out our list of the best website builders for an easy way to create a professional site without coding.

If you are building from scratch, the most common languages used alongside HTML include:

CSS

Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) controls how your site looks. If HTML defines what the content is, CSS defines how it’s presented—fonts, colors, spacing, and layout.

In practice, CSS lets you set typography and color systems, create responsive layouts with Flexbox and Grid, and tailor components for different screen sizes with media queries. Modern CSS also supports features like container queries, logical properties, and native nesting, which reduce reliance on heavy frameworks.

JS

JavaScript (JS) adds behavior and interactivity on top of HTML and CSS. It listens for events (clicks, scrolls, form input), updates the DOM, fetches data, and powers components like tabs, modals, carousels, and dashboards.

For forms, HTML5 provides built-in validation for required fields and formats; JavaScript enhances this with real-time checks, custom error messages, and conditional logic. JS also enables dynamic content—like popups, accordions, and hover-activated menus—based on user interactions.

Beyond the browser, JavaScript can run on servers (Node.js) to render pages, handle APIs, and share code between client and server when needed.

PHP

Hypertext Preprocessor (PHP) is a server-side scripting language. It executes on the server, pulls data from databases like MySQL, and outputs HTML that the browser displays.

PHP powers many content-heavy and ecommerce sites because it can handle user accounts, orders, and content management. Platforms like WordPress are built with PHP, which is why you can create dynamic pages, templates, and plugins that generate HTML on the fly.

Ruby on Rails

Ruby on Rails is a full-stack web framework that follows the Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern. The Model manages data and business rules; the View outputs HTML/CSS/JS for the interface; and the Controller coordinates requests and responses between them.

Rails emphasizes convention over configuration, which helps teams build secure, database-backed apps quickly while still delivering clean, accessible HTML to the browser.

Examples of HTML Websites That Still Work Today

Pure HTML-only sites are rare today because HTML by itself is limited. Still, a few no-frills sites thrive by keeping things simple and fast.

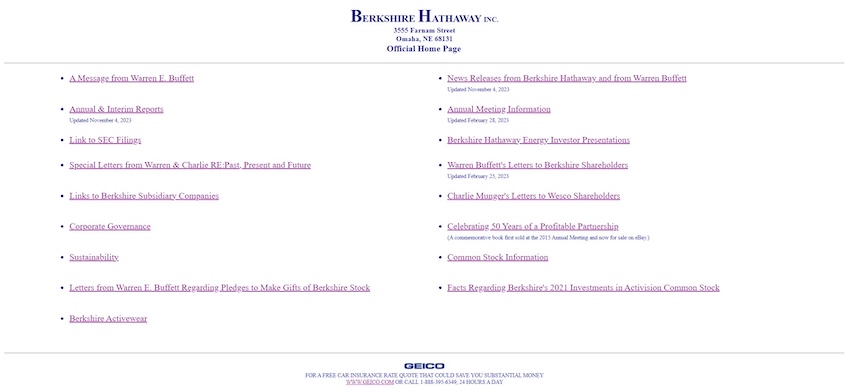

Berkshire Hathaway

Berkshire Hathaway is a holding company shaped by multiple mergers, including a pivotal one in 1955 with Hathaway Manufacturing. Warren Buffett began buying shares several years later and took control in 1965, building the conglomerate known today, with subsidiaries like GEICO, Dairy Queen, and Duracell.

Its site’s raw, text-first HTML is deliberately different from the polished consumer sites of its subsidiaries. Berkshire Hathaway’s primary audience is shareholders, not shoppers.

The homepage functions as a straightforward navigation hub—no hero image or marketing copy, just a tidy list of links.

Despite its minimalism, the site follows solid UX principles: clear information architecture and fast access to reports, SEC filings, and stock details.

That no-frills approach makes the site extremely quick to load and easy to use, regardless of connection speed or device.

Takeaway: Nail simple, intuitive navigation before layering on advanced visuals. Clear menus help visitors (and search engines) find what matters quickly, which can improve engagement.

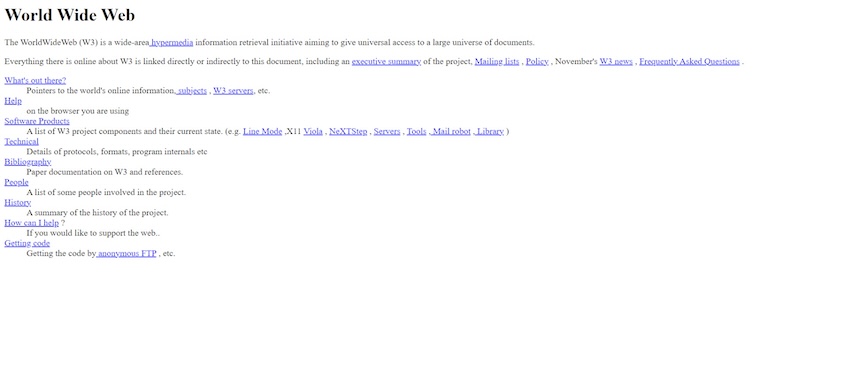

The World Wide Web Project

This is the first website you can still visit—sort of.

Launched in 2013 by CERN, The World Wide Web Project is a restoration of the original site published in 1991 by Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web.

By 1993, CERN opened the web to the public. The number of sites climbed rapidly through the mid-1990s; by 1998—around the time Google launched—there were millions of pages online.

Most early sites weren’t archived, but this one survives and shows a timeless pattern: a clean homepage listing key topics, each with a brief explanation and a link.

Subpages follow the same structure, effectively creating an early version of a mega-menu. Rather than overwhelming visitors with every link at once, the site groups content into sensible categories and routes people to focused subpages.

Each level branches into more specific topics via hyperlinks, making it easy to drill down to exactly what you need.

Takeaway: Thoughtful submenus are essential for large, content-rich sites—especially ecommerce. Use dropdowns and mega-menus to keep navigation tidy and scannable.

Lochie Axon

As a portfolio, Lochie Axon’s site is intentionally minimal—nearly pure HTML.

Note: there’s a touch of CSS for stylized text at the bottom, but it’s so light we’ll treat the page as essentially HTML-only.

The header introduces the designer and specialization; the bulleted links immediately route visitors to featured projects. Simple text links also point to social profiles for quick context.

On a site this sparse, small design flourishes matter. The playful smiley and subtle typography cue personality without sacrificing speed or clarity—signaling the creator knows minimalism is a choice, not a constraint.

Bottom line: the page accomplishes its goal—drive clicks to portfolio work—while staying fast and distraction-free.

When a Plain HTML Page Makes Sense (and When It Doesn’t)

Use a mostly-HTML approach when you need a lightweight, unchanging page (e.g., a simple company profile, a single-purpose landing page, or a status notice). Add CSS for readability and accessibility, and only the JavaScript you truly need.

Choose a fuller stack—CSS, JavaScript, and a server-side language—when you need user accounts, forms with dynamic logic, search, a blog or CMS, ecommerce, analytics-driven personalization, or integrations with third-party services.

Modern HTML Best Practices (Quick Checklist)

- Use semantic elements (

<header>,<main>,<nav>,<article>,<section>,<footer>) so screen readers and search engines understand your layout. - Add accurate

alttext to images and use proper label associations for form controls to improve accessibility and SEO. - Make pages responsive with the viewport meta tag and CSS Grid/Flexbox. Test on phones, tablets, and desktops.

- Prioritize performance: compress images, use modern formats where appropriate, and leverage native attributes like

loading="lazy"for images. - Keep navigation predictable and scannable; use descriptive link text (not just “click here”).

- Validate HTML and CSS, and lint JavaScript to catch errors early.

- Favor progressive enhancement: start with accessible HTML, then layer in CSS and JS so core content still works if scripts fail.