Whether you’ve heard the term before or not, nameservers are the quiet workhorses that make the internet usable.

In simple terms, nameservers spare you from memorizing numerical Internet Protocol (IP) addresses for every site you visit. Without them, you’d have to type an IP like 141.193.213.11 every time you wanted to open a page—something most of us would never do.

Instead, a nameserver translates the address behind the scenes, so you only need to remember the human-friendly domain name.

That’s the gist. But there’s much more to nameservers—and understanding the basics will help you run a faster, more reliable website.

What Is a Nameserver?

A nameserver is a specialized server that maps domain names to their corresponding IP addresses. When you enter a URL in your browser, a nameserver helps route that request to the correct web server by connecting the domain name with the IP address of the web host.

To appreciate what a nameserver actually does, it helps to peek under the hood at some of the less visible—but essential—internet plumbing.

Nameserver vs. DNS

The Domain Name System (DNS) is the global, distributed database that keeps track of which domain names point to which IP addresses. A domain needs one or more nameservers to host and serve its DNS records—this typically starts the moment you register the domain with a registrar.

Your domain registrar sets the initial nameservers for your domain and gives you a control panel to view or change them. The best domain registrars make this easy with DNS and nameserver management tools.

Think of DNS like a constantly updated internet phone book: a catalog of domains and the computers and services behind them. With this map in place, browsers know where to send your request.

So, DNS is the overall system for routing traffic; nameservers are the specific servers that store your domain’s DNS records and answer questions about them.

Those records are organized on nameservers so your browser lands at the right site when you type an address.

Key moving parts within DNS include:

- Nameservers

- Domain registrar

- DNS records

- Web-based services like web-hosting platforms

DNS records contain the data that directs traffic—most notably the IP address of your website. Nameservers host, store, and serve those records when asked.

Common record types you’ll see on a nameserver include A records (IPv4 addresses), AAAA records (IPv6 addresses), CNAME records (aliases), NS records (the domain’s nameservers), MX records (mail servers), TXT records (text data like SPF/verification), SRV records (service locations), CAA records (which Certificate Authorities may issue SSL certificates), and increasingly HTTPS/SVCB records (used by modern browsers for performance and new protocols).

Why Nameservers Matter

Nameservers directly affect whether your site can be found quickly and reliably.

In practice, nameservers are DNS servers running in data centers or cloud networks, often anycasted worldwide for speed and resilience. They store and serve DNS records for the domains they manage, and many are operated by web hosting platforms or dedicated DNS providers.

By performing DNS resolution, nameservers let you type a URL instead of a numeric address and ensure your browser gets the right IP to load the site. Without accurate, responsive nameservers, your website can feel slow, flaky, or completely unreachable.

Most people don’t think about nameservers until they migrate hosts, set up email, add subdomains, or troubleshoot downtime—then they become mission-critical.

A brief overview of how nameservers work

Every device connected to the internet has an IP address. That’s great for machines, but not for humans. Nameservers bridge that gap by converting domain names into the correct IPs.

When you request a website, your device and browser use the broader TCP/IP networking stack to reach out and find the IP address for the domain you typed.

Behind the scenes, your resolver (usually provided by your ISP or a public DNS like 1.1.1.1 or 8.8.8.8) asks the DNS hierarchy—root servers, then top-level domain (TLD) servers, then the domain’s authoritative nameservers—until it gets the final answer. Caching keeps things snappy on subsequent visits.

If everything checks out, the correct IP address is returned to your browser so it can connect to the web server and load the page. If anything breaks along the way, you’ll see an error like “This site can’t be reached.”

In short: find nameserver > fetch DNS record > return IP > load website.

When Do You Need To Know Your Website’s Nameservers

Most site owners can ignore nameservers if they bought and host the domain in the same place. But nameservers also define who controls your DNS zone—so knowing them becomes important whenever you change where your DNS is managed.

Here are common scenarios where you’ll want to look them up:

- When you are changing your domain’s nameserver.

- When you’re pointing your domain name to a new web hosting service.

- During the troubleshooting of DNS issues like partial DNS failure.

- When domain names are moved from one registrar to another, which requires the identification of the DNS records currently associated with the domain name.

- When you’re customizing nameservers.

Your hosting or DNS provider dashboard will usually show your current nameservers and let you manage, edit, or replace them.

If your domain is registered elsewhere, you’ll need to log into that registrar to update the nameservers on file for the domain.

Changing nameservers

Changing nameservers is how you point a domain to a different DNS host (often part of moving your site to a new web host while keeping the same domain).

Here’s the typical flow:

- Log into your domain registrar and open the DNS or Nameserver settings for the domain.

- Select the option to use custom nameservers and paste in the new nameservers from your hosting/DNS provider (usually at least two).

- Save/confirm the change. If you manage DNS records at the new provider, make sure all required records (A/AAAA, CNAME, MX, TXT, etc.) are present before or immediately after switching.

- Wait for DNS propagation. Most updates begin resolving within minutes and broadly propagate within a few hours, but they can take up to 24–48 hours worldwide depending on TTLs and caching.

- Verify the change with a lookup tool (examples below) from multiple networks if possible.

Propagation isn’t instant everywhere. Local device caches, ISP caches, and record TTL (time-to-live) all influence how fast the new answer appears globally.

Other uses

Many registrars (e.g., GoDaddy, Namecheap) let you set up custom or vanity nameservers for branding—such as ns1.yourbrand.com. To do this, you’ll register the custom nameserver hostnames at the registrar and point them to your DNS provider’s IPs (“glue” records if the nameserver sits under the same domain).

Exact steps vary by registrar. Check their help docs or contact support for details on registering custom nameserver hosts and updating the related DNS.

How to Look Up the Nameservers of a Website

Nameservers are public. You can look them up with tools like WHOIS Domaintools and Google Dig (DNS lookup).

A WHOIS search may also show the domain owner’s contact details unless domain privacy is enabled by the registrar.

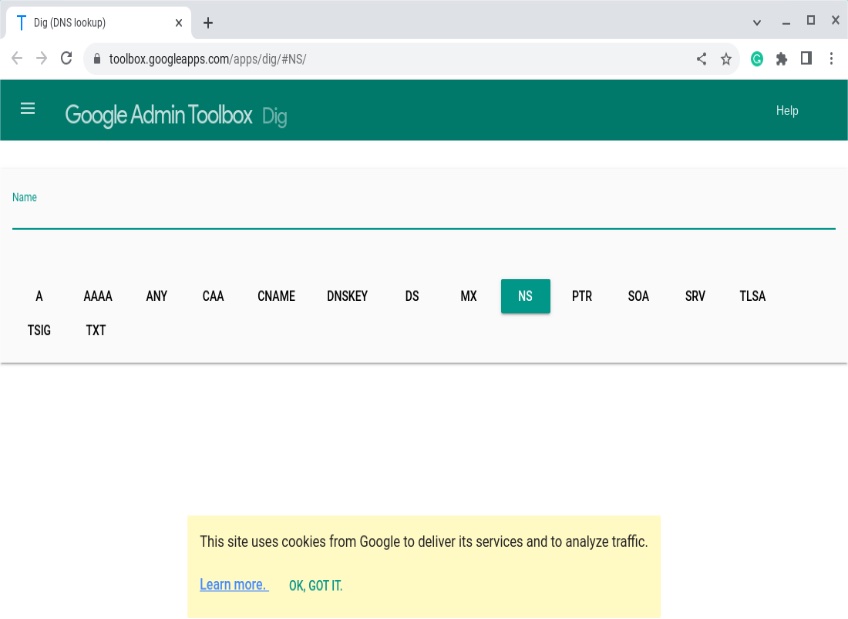

Using the Google Dig tool’s NS lookup, I queried quicksprout.com by typing the domain in the search bar and selecting the NS option, which returned its nameserver information immediately.

Selecting Raw View exposes additional technical detail about the response.

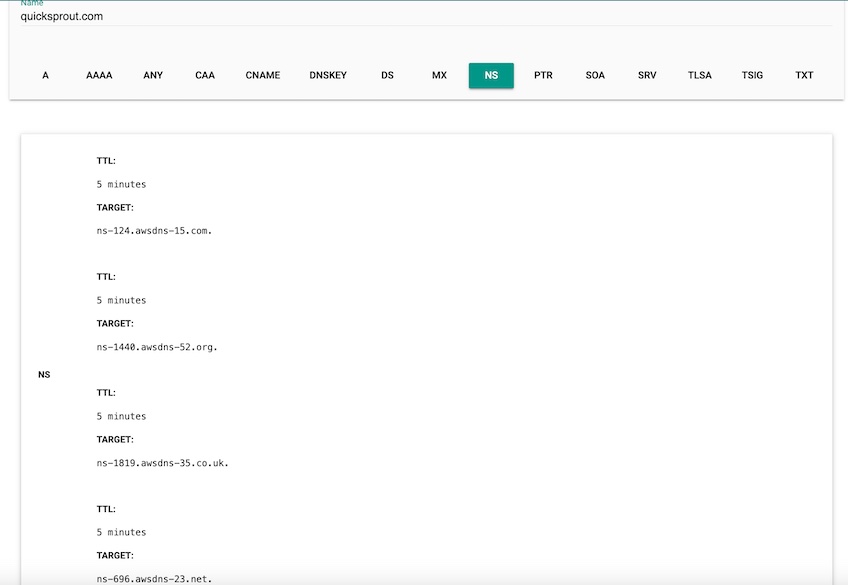

In my example, the tool shows that quicksprout.com uses four nameservers:

- NS ns-124.awsdns-15.com.

- NS ns-1440.awsdns-52.org.

- NS ns-1819.awsdns-35.co.uk.

- NS ns-696.awsdns-23.net.

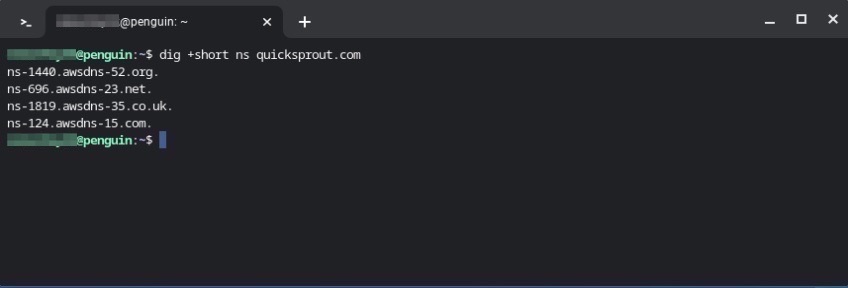

You can also query nameservers from your own computer using command-line tools.

On Linux or macOS, run dig +short ns yourdomain.tld in Terminal. If a firewall or router blocks the dig utility, you may need to try from another network or use a web-based tool.

High-traffic sites typically publish multiple nameservers to balance load and build redundancy. Spreading queries across several nameservers removes a single point of failure and improves uptime.

Using nslookup commands

If you want more verbose output (including which server answered), try nslookup.

Open PowerShell (Windows) or Terminal (macOS/Linux) and run: nslookup -type=ns yourdomain.tld.

For example, I queried quicksprout.com the same way.

nslookup also distinguishes between authoritative and non-authoritative answers. Authoritative nameservers host the domain’s zone files and provide the definitive response (like the A record mapping a domain to an IP). Non-authoritative servers usually return cached results.

Multiple nameservers don’t just improve performance—they also improve security. Attacking a single DNS endpoint is easier than taking down a distributed, anycasted network of nameservers.

Most registrars ask for primary and secondary nameservers at minimum, so if one goes offline, another can answer.

Quick troubleshooting tips

If a change isn’t showing up, try lowering TTLs before a planned switch, then raise them after. Flush local caches (ipconfig /flushdns on Windows; sudo dscacheutil -flushcache && sudo killall -HUP mDNSResponder on macOS) and test from a mobile network or DNS like 1.1.1.1/8.8.8.8. Errors like SERVFAIL often point to DNSSEC or upstream issues; NXDOMAIN usually means the record doesn’t exist at the authoritative server.

Do nameservers affect SEO or site speed?

Search engines don’t rank sites based on which nameservers you use, but slow or unreliable DNS can increase initial connection time and hurt overall experience. Using reputable, globally distributed DNS with proper caching and security (and enabling DNSSEC where supported) helps ensure consistent performance and trust.